When you have a wood burner and rely on it for heating your home, you can soon become preoccupied with thinking about ‘bois de chauffage’, the wood to burn on it. Firstly, what type is best? Sure, a hardwood like oak is rated the highest but as a result, it’s more expensive than a ‘fruitier’, like cherry say, or walnut. And then there’s the question of how you buy it in. I don’t mean ordering it on line, which is probably what I’ll do when the time comes as I’ve already located several suppliers who can supply the Plazac area at competitive prices. No, what I’m talking about is how it’s delivered – the length and diameter of the pieces and whether it comes conveniently packaged and wrapped on pallets or loose in bulk on a truck or trailer. Whatever you decide to go for ends up affecting the price, as I’ll explain below.

You’d think that wood would be sold by weight, but this being France of course, it’s not that simple. It’s sold by volume, so you just have to trust in the reputation of the seller that what you are getting is ‘value for money’ compared to other suppliers. In any case, weight is problematic because it can change while volume remains constant due to moisture content and all good suppliers therefore guarantee that their wood has been dried for at least two years and has a maximum stated moisture content. But things become even more complicated when the wood is cut down in size.

A standard cubic metre of wood consists of lengths of wood each of length 1 metre stacked one on top of the other to fill the space. This is what is known in France as a ‘stère’, the old metric system word for a cubic metre. But most people can’t fit 1 metre lengths of wood into their wood burners so want it cut into shorter lengths, of say 50 cm (half a metre, which my stove and most other modern wood burners can accept) or 33 cm. However, the smaller the pieces the original 1 metre lengths are cut into, the more they can ‘settle down’ by fitting more efficiently into the space available, so depending on the length the original pieces are cut into, the more the final ‘delivered’ volume changes ie if they are cut down to 50 cm, the volume they take up shrinks and if they are cut shorter to 33 cm, it shrinks even further. But even though the volume of the wood has reduced, the same ‘amount’ of wood in standard 1 metre lengths (or put another way, the same energy equivalent) is being supplied. So, although wood is sold in ‘stères’, depending on how you ask for it to be pre-cut, the actual volume in cubic metres that is delivered is different ie the volume is less the smaller you ask for your logs to be cut down.

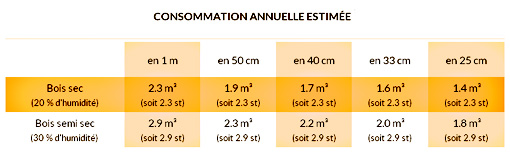

The suppliers use standard conversion factors for each length of cut below the ‘standard’ 1 metre, which I can’t find for the moment, but the following image shows what I’m talking about. It’s an ‘estimate’ for the annual consumption of cut logs for heating a small/medium house with poor/average insulation in the Dordogne to 20 degrees Celsius with a modern wood burner and reflects what I might expect to need for heating my house, for example.

The first thing to note is the extent to which increased moisture content in the wood reduces its energy efficiency. The image shows that 2.3 st of 1 metre wood with 20% moisture content is needed to achieve the required level of heating, but to provide the same amount of heat, 2.9 st of wood with a moisture content of 30% is required. So with an incremental increase in moisture content of 10%, over 25% more wood is needed to generate the same amount of heat. This interests me greatly because at the moment I’m burning old wood from my garden none of which has been set aside to dry out (although much of it is dead wood) and some, even, is being burnt after only having been cut just a few days before. This would suggest that I’m not working my wood burner in a very efficient way at all, but the saving grace is that at least the wood isn’t costing me anything.

Now to the question of how ‘delivered’ volume changes with the length of cut of the logs. Looking just at the top ‘20% moisture’ row, you can see that for each log length, the same quantity of wood in ‘stères’ (2.3) is needed to warm the house up by the same amount no matter what log length is supplied. However, the ‘delivered’ volume reduces as the log length gets smaller. So by definition, if 1 metre lengths are supplied, the volume delivered is 2.3 cu/m but if the lengths are cut in half (into 50 cm logs) the ‘delivered’ volume drops to 1.9 cu/m. Similarly, 40 cm logs see the volume drop to 1.7 cu/m, 33 cm logs to 1.6 cu/m and so on.

So as you would be buying the same volume in ‘stères’ at each log length, you might expect to pay the same total money amount even though the actual ‘delivered’ volumes would be smaller as the log length is reduced. However, this is not so and the reason is that as the supplier has to do more work cutting the original 1 metre lengths into smaller and smaller logs, he naturally charges extra for the smaller lengths. It therefore follows that if you can accept logs in longer lengths which you then cut up yourself, you will end up paying proportionately a bit less for your wood.

Then there’s the question of delivery. The suppliers advertising on the internet usually favour delivering the wood to you on a pallet wrapped in plastic and probably for most householders, this is the most convenient way. However, convenience as always comes at a cost and wood bought-in in this way naturally costs more per ‘stère’ than if the supplier can just draw up to your house with the wood loose in bulk on the back of a truck or a trailer that they can then just empty out onto your lawn. To make up for that, they usually specify a minimum order size for wood purchased in bulk but this needn’t be beyond the scope of the average householder who will then, of course have to spend time himself moving and stacking the wood either under a shelter or to a position where it can be protected with a waterproof cover.

So you can see that there are quite a few factors to be taken into account before deciding on your wood supplier and it can become a bit of a nightmare comparing one against another, especially if any just ‘happen’ to be selling wood with a slightly higher moisture content for some reason or another.

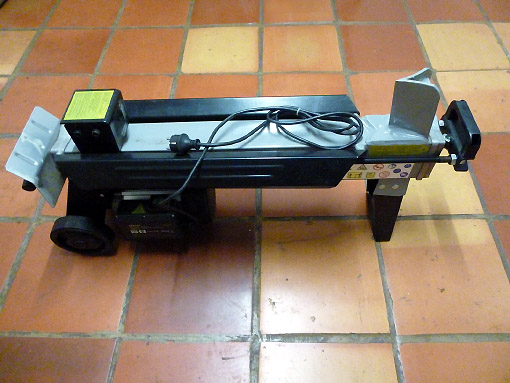

Now you may be wondering what brought all this stuff on and where it might be leading to, especially as I don’t need to buy any wood in just yet because of the amount that I have available from my garden. The thing is, I will need to at some point in the not too distant future when my own wood runs out, so I need to make sure that decisions I take now will be the right ones. Specifically, where I’ve been cutting old, dead trees down, I’ve been left with several quite long, large diameter stumps which, of course, are still an excellent source of wood. However, for them to be usable, they need to be cut into shorter lengths and then split into logs of manageable proportions and this would require the use of a hydraulic log splitter as they are much too big to split using an axe. At least I think so, anyway. But log splitters come at a price – at least 249€ for a new 5 tonne model on Ebay, and if after splitting my tree stumps I would then have no further use for it, could I justify such an expenditure, especially when I could hire a splitter for a day to do the job for around 20-30€?

The cost of a new model would be quite a large sum to make up by buying in rough, large diameter logs compared to pre-cut smaller diameter ones, but maybe not so if a good ‘used’ model was available on Le Bon Coin, for example. Well, to cut a long story short, the other day I came across a 5 tonne model that was a year or so old but had never been used, and for only 120€! The catch was that it was down south in the Ariège but I decided that it would be worth it even with the additional cost of the fuel there and back, and in any case, I thought that a trip that got me out of the house at this time of the year, and with a sight of the Pyrénées thrown in to boot, would be nice. And so it was that I hit the road early yesterday morning.

The journey itself turned out to be something of a nightmare due to incessant heavy rain that reduced visibility north of Toulouse to almost the rear lights of the vehicle in front, but I got there and back safely, with my purchase stowed in the back of my car. I didn’t have much time to test it because it was dark outside pretty soon after I got back with it. However, I did succeed in splitting a couple of smaller logs that I already had indoors, in my kitchen, where I took the shots shown below, so I knew that it worked and couldn’t wait to put a few bigger logs through it to see how it would do.

And that’s what I managed to do today, before it began to rain forcing me to pack up and come indoors. After I’d chopped it up into manageable chunks, it made short work of a large length of tree trunk that I’d had under cover for some time so I now know that it’ll handle all of the other large diameter lengths that I’ll have that otherwise I’d have had difficulty in dealing with. And at the price I got it for, I think that the expense was justified, especially as it now means that with both my ‘tronçonneuse’ (chain saw) and my ‘fendeuse de bûches’ (log splitter) I’ll be able to save money on my future purchases of wood when my own supply eventually runs out 😉

A quick footnote to finish off – as readers know, unlike in English, all French nouns have a gender which is either masculine or feminine. The French word for ‘log splitter’ is the first that I have come across that can be either – a log splitter can be referred to as either ‘un fendeur’ (masculine) or ‘une fendeuse’ (feminine). Interesting, that I think.

By the way, the Pyrénées looked fantastic yesterday, with a covering of snow and shining brilliant white, silver and gold under a bright sunny sky. Made the journey worth it just by themselves 🙂